It’s pretty easy to just slide a shell into your trusty shotgun and go about your business.

But what’s a shotgun shell made from? How is it constructed? How does it really work?

The answer to all these questions and more as we walk you through Shotgun Shells 101.

Anatomy Of A Shotgun Shell.

The usual shotgun shell is made up of the following elements:

1. The Primer

2. The Powder

3. The Wad

4. The Shot

5. The Case

Let’s have a look at them, one by one.

The Primer

Primers for shotgun shells are larger than those of ammunition for rifles and pistols. There’s usually a metal cuff at the base of a shotgun shell. On the bottom of that base is the primer, which consists of the anvil, primer cap, and priming compound. The firing pin of the shotgun striking the primer results ignition of the powder in the shell.

The vast majority of shotgun shells use a type “209” primer. FUN FACT: Most modern in-line muzzleloaders also use this same primer.

The Powder

After being ignited by the primer, any chemical formulation that propels the wad and the shot out of the barrel is the powder. Smokeless powder in the modern age—black powder in the old days.

Modern smokeless powders—sometimes containing up to 50% nitroglycerin—are more efficient than black powder used in earlier shotgun shells—so, very little space in the shell is actually taken up by the powder. Shotgun powders are typically fast-burning ball or flake-type powders, unlike the slower burning extruded powders used in large rifles to more gradually build up extremely high pressure levels.

The Wad

Responsible for sealing propellant gas forces behind the shot for improved velocity, the wad separates the powder from the shot.

Nearly all modern shotgun wads are made of plastic instead of fiber. Many are now using plastic that is more environmentally friendly. Plastic wads expand upon firing. Because fiber wads are compressed to fit in the cartridge, they are loaded at a higher pressure, creating more recoil than plastic wads.

The Shot

Simply put, shot is the projectiles in a shotgun shell. A shotgun does not ever fire a “bullet”. An individual piece of shot is called a pellet. The size and kind of shot/pellet depends on the desired application.

Larger shot carries more momentum and can often travel greater distances, but gives the shooter less opportunity to hit a smaller target than smaller shot which contains more pellets per load.

While shot has traditionally been made of lead, it is also made from steel, tungsten, and bismuth due to restrictions on lead, particularly near water. It can also be copper-plated to help pellets keep their shape when fired.

The designation for sizes of shot is divided into two categories: bird shot and buckshot.

The designations are on two different scales. Bird shot is smaller, and like buckshot—the larger the number, the smaller the pellet on the basis of diameter. For example, #9 bird shot is .08 inches in diameter, and #8 bird shot is .09 inches in diameter. #3 buckshot is .25 inches in diameter while #1 buckshot is .30 inches in diameter.

The two scales are independent of each other. For example, #4 bird shot is not the same as #4 buckshot (being nearly half the size of buckshot.

At the larger end of the scale for bird shot, letters take the place after the number 1—including B, BB, and T. Zeros take the larger end of the scale with buckshot, and an additional zero is added for each larger size pellet—as is explained in the buckshot section of this article.

There is a wide variety of shot available for shotgun shells. Here are a few common ones.

BIRD SHOT

BIRD SHOT

When using shotguns for hunting, the size of shot must be selected on the basis of not just the range, but also the type of game being sought.

The shot has to be able to reach the prey, but also to penetrate far enough to dispatch it.

Lead shot is preferred by most, but in some situations might have to be substituted with steel, tungsten, or bismuth due to restrictions on lead. California now requires that all game be taken with non-toxic shot, citing concern for raptors who often feed on the carcasses of hunting-killed birds.

Steel is a good substitute when lead can’t be used, but care must be shown when using either older shotguns or choke tubes due to the damage steel can cause to them. However, increased pressure of steel shells is more often the culprit than the shot when damage occurs. Waterfowlers often use chrome-lined barrels and high quality choke tubes to mitigate the damaging effects of steel-on-steel.

Low-pressure sporting and hunting versions of shells with steel shot can be used, if needed.

Tungsten is also a good substitute for lead, but being a very hard metal must also be used with care in older shotguns. Tungsten can be alloyed with nickel and iron to soften the shot—although these alloy shells are far more expensive than lead ones.

Bismuth is in between steel and tungsten in density, and in cost.

BUCKSHOT

Larger sizes of shot are referred to as “buckshot.” This shot must be carefully placed into the shell, as opposed to just being poured in.

This type of shot is used for hunting larger game, like deer—which leads to the name, buckshot. It’s also commonly used for feral hogs, bear, and coyotes.

The size of buckshot is designated by letter or number. The smaller the number, the larger the shot. Shot that is larger than size 0 is given additional zeros, so “00” is larger than “0”.

00 is referred to as “double aught” and is the most common size of buckshot. The most commonly produced buckshot is a 12-gauge, 00 buck shell holding 9 pellets. It’s used for self-defense and hunting medium to large game.

“00-buck” is the standard shotgun used by police and militaries around the world. It can be extremely effective. For reference, a single load of 00-buck is roughly equivalent to an entire magazine of .32 Automatic being fired at the same time based on velocity and projectile diameter. 00-buck has been known to over-penetrate or cause excess damage beyond and around the target.

Shells for buckshot can be tailored by varying size of shot, pellet count, length of shell, and powder to fit specific weapons and purposes.

Reduced recoil shells for buckshot are increasing in both popularity and availability. Low-recoil 00 shells allow for faster follow-up shots, and are useful in conditioning shooters not yet accustomed to full recoil shooting.

SLUGS

SLUGS

Slugs are shotgun shells containing one single projective. Typically, a slug is a lead or copper-covered projectile, sometimes with a plastic tip.

Modern slugs are designed to be fired from shotguns with rifled barrels, or rifled choke tubes, in order to provide spin stabilization of the slug while in flight. In the absence of such rifling, the slug must be self-stabilizing.

Saboted slugs make use of a plastic sabot which engages with a rifled barrel to create a ballistic spin on the slug. The sabot keeps the slug centered while being spun by the rifling of the barrel. Saboted slugs fired from a rifled barrel are typically far more accurate that non-saboted slugs fired from a smoothbore barrel.

NOTE: A slug should never be fired when using a full choke. A cylinder bore or cylinder choke is recommended when firing a slug.

The Case

Also commonly called a “hull,” the case contains all the other elements of a shotgun shell. The case can be made of many substances. The most common at present is plastic, but the case can also be made of paper, or in rare cases, brass.

Shotgun shell cases come in different lengths to accommodate the type of firing desired. The chamber of a shotgun is made for only certain sizes of shell. So, the length of the shell being loaded is very important.

Loading a shell that’s too big could result in a greater than required pressure and cause damage to the shotgun, and injury to the shooter.

Most modern shotguns have a 2 ¾ or 3-inch chamber. Old English shotguns or older domestic shotgunshave a 2.5-inch chamber. It’s possible to shoot a smaller shell from a larger chamber, but don’t shoot a larger shell from a smaller chamber. The best practice is to shoot shells properly sized to the chamber of the shotgun you’re firing.

It’s important to note that the length noted on a box of shotgun shells is the length of the OPEN case, not the closed (crimped) case. Don’t simply take out a rule and measure the length of an unfired shell. The number printed on the shell should not exceed the measurement on the barrel.

3.5-inch shells are often called “magnum” shells, most commonly used by turkey and goose hunters who are wanting to send an especially large payload of birdshot at a far away target.

While it is safe to fire shorter shells in a longer chamber, this may cause some feeding or ejection issues in semi-automatic models that use gas pressure from the round to work the action.

Now, here are a few other terms that factor into your understanding of shotgun shells that you really should know.

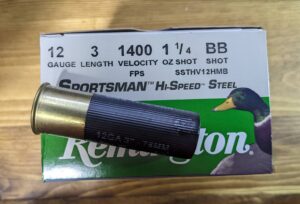

GAUGE

Rifles and handguns are measured by caliber (the internal diameter of the barrel) which is nearly equal to the diameter of the projectile fired (for example, a 308 Winchester shoots a bullet that is .308 in diameter.) Shotguns are measured by the gauge, which is the fractions of a pound that a round, pure lead ball would be to take up the internal diameter of the barrel.

So, for a particular gauge, the question is “How many lead spheres of this diameter would it take to weigh a pound?” Increasing the diameter makes for a larger sphere, and therefore takes less of those spheres to equal a pound. So, a “1 gauge” bore would be the diameter of a one-pound lead ball. A “20 gauge” shotgun has a bore that’s the size of a lead ball weighing 1/20th of a pound.

That’s why as gauges get higher, they get smaller in size. 12 gauge is the most common gauge of shotgun by far, followed by 20 gauge, but other sizes in use are 10, 16, and 28. Gauges of 4, 8, 24, and 32 are largely collector’s items.

The only common exception to this is the .410, which is really just a bore diameter, not a true gauge measurement.

DRAM

Dram is a measure of powder charge, based on the avoirdupois system of measurement (pounds and ounces.) In shotgun shells, it was a measurement of the amount of black powder contained in a shell as a way of designating the power that shell would contain.

Smokeless powder is much more potent than black powder, this designation is an equivalency to the amount of black powder it would take to deliver the same charge as the smokeless powder in the shell. In modern shells, it gives an equivalence in modern shells to the amount of black powder measured in the avoirdupois system. Some boxes of shells still list “dram.” Many do not.

CHOKE TUBES

The “choke” is a small constriction built into the last few inches of the barrel of a shotgun, intended to funnel or tighten the pattern of the shot.

Because shot projectiles have a tendency to spread or separate from each other rapidly, a choke is necessary to control or concentrate this spread for firing at various distances and types of targets.

Older shotguns have chokes that are built into the barrel, or fixed, which means they can’t be altered.

Newer shotguns most often can be altered with multiple “choke tubes” which can be screwed in and out of a shotgun with ease. These choke tubes make a shotgun more versatile in terms of being able to create a more effective shot in numerous situations.

Choke tubes go from “most open” to “most constricted” with the common progression of Cylinder, Skeet, Improved Cylinder, Modified, Full, and Extra Full.

Screw-in choke tubes allow one shotgun to be used for a number of different situations and applications.

While the mechanical operation of a choke seems simple enough, always heed warnings and instructions from the choke tube manufacturer. Not all chokes can be used with steel shot, and generally choke tubes are only designed for specific shot sizes.

In terms of effective use, the principles of the shotgun shell must be learned and understood for the maximum in effectiveness and safety, like any other type of ammunition. Knowing all the aspects can greatly increase your precision and desired outcome on a more frequent basis.